This article draws on the experiences of the AHRífunded project on Latin(o) American New Media Art, and makes a series of observations and recommendations regarding the exhibition spaces for digital artwork, the uses of social media for curation and engagement, and future possibilities for Europe-Latin(o) American artistic collaborations. Involved in the exhibition were four leading artists from Latin America and the US: Brian Mackern from Uruguay, Bárbara Palomino from Chile, Marina Zerbarini from Argentina, and Ricardo Miranda Zúñiga from the US.[1]

FIG 1. Brian Mackern signature Santa Rosa at FACT

FIG 1. Brian Mackern signature Santa Rosa at FACT

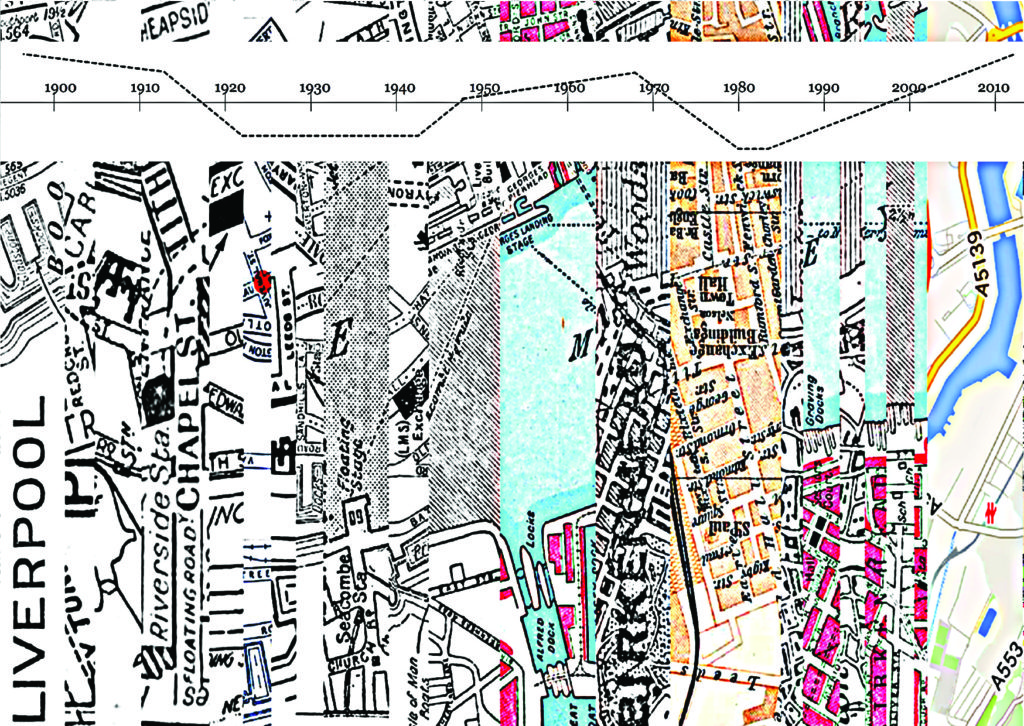

FIG 2. Memoria histórica de la Alameda at FACT

FIG 2. Memoria histórica de la Alameda at FACT

We hope that this article particular interest to museums, art festivals, art galleries, community media groups, media labs, digital artists as practitioners, and professional associations working with new media. Particular interested parties, several of whom have contributed to this document, include FACT (Foundation for Art and Creative Technology), the Independents Liverpool Biennial, the E-Poetry Festival, the Centro Cultural Jorge Luis Borges, the Cabildo de Montevideo, and the Escuela de Defensa Nacional in Buenos Aires.

Exhibition Spaces for New Media Arts: Combining Virtual and Physical Space

This section draws on the experiences of the project in selecting and working with a variety of venues for new media arts events. The various artworks, interventions and events related to cityspace, and invited the audience to re-think the urban space that surrounds them. Audience reactions were captured through social media, questionnaires, and follow-up workshops.

Regarding exhibition spaces, two central concerns had to be addressed. Firstly, how can digital art b often containing components that exist in virtual space b be exhibited in physical space? This has been a constant in debates on the exhibition of new media arts.[2] Secondly, given that the artworks chosen were originally developed in a specific city space, a fundamental challenge was how to translate that to another city (Liverpool). When taken out of their immediate environment, how do these place-based works function?

The project concluded that, as regards exhibition spaces for new media arts, the venues selected needed to be flexible, and able to accommodate both the digital and the place-based elements of the art works. The selection of The Box at FACT, for example, lay in its flexible furniture, which could be suited to the different artworks: for instance, for Brian Mackernbs Santa Rosa Storm, it was possible to arrange the furniture to create the impression of a central aisle of a church leading up to an altar [FIG 1]. Other venues were chosen due to their emerging nature, in that they were recently renovated spaces that were first turning to cultural and artistic exhibitions, and so presented the opportunity to showcase new art forms, such as the Cabildo in Montevideo.

Drawing on the experience of not only presenting exhibitions but also running multiple workshops in various spaces and locations, the benefits of presenting digital artworks in physical spaces were found to be:

- Combination of the physical with the virtual. All of the artworks selected included physical (offline) interaction as well as online interaction. The exhibiting of the works in a physical place meant that audience interaction could take multiple forms, including the tactile as well as the virtual. Interaction with physical artefacts, such as body movement of the spectators that caused fluctuations to a live flame in the case of one of the artworks, meant that the audience experienced the works on multiple levels.

- Enrichment of the artworks through negotiating with the spaces. Adapting the artworks and the associated events to the local circumstances of the space led to creative dialogues with the artists, and a richer understanding of the artworks. For instance, the adaptation of the altar used for one artwork into a plinth for displaying robots in another artwork fed into discussions about the creative re-use of materials and spaces. In the case of another work, the use of three screens also redefined the interactive nature of the work - since it was not originally designed to be exhibited that way - meaning that the curatorial decision, and the creative use of the space generated a new version of the same artwork.

- Greater possibilities to engage the public in practice. Running a series of face-to-face events, including the exhibition but also artist talks, workshops and interviews, rather than solely presenting the works online meant that groups who might not have engaged exclusively online were brought into the discussion. For instance, workshops held at the MediaLab at FACT with the Veterans in Practice enabled the sharing of best practice, and brought into dialogue not only the members of the group who already engage in online media, but also those who work with more traditional media.

The workshops that Claire Taylorbs project ran with ViP have enthused one of our members to try get involved in the art world and think about art differently [...amp;] It helped with the project getting people to think about different way they collect information and how this can be organized as a map.

Paul Dean, Art Psychotherapist,B Veterans in Practice.

The challenges of exhibiting digital artworks in physical spaces were found to be:

- Technical issues in re-vamped/recuperated spaces. Technical issues, particularly as regards internet connectivity, wiring and equipment were a factor in the choice of venues. In the initial planning of events, some venues were viewed which would have been ideal as regards integration with the cityspace, and the recuperation of urban spaces for artistic purposes, but which lacked the infrastructure to support digital interventions. There is, therefore, a playoff between aesthetic choices as regards venues, and practical choices as regards suitable equipment and connectivity to host digital artworks. Creative ways of working round restrictions in the venues, and, in particular, the creative use of low-tech as a resistant gesture can be one way of meeting this challenge.

- Making the intervention attractive. As has frequently been noted in curatorial discussions on digital art (Stallabrass 2003: 120), it is important to avoid simply setting up a digital artwork on a computer, since this is not an attractive offering to the public. Instead, a fully rounded, attractive offering, including non-digital elements, tactile elements, and playful interaction must be provided to ensure that the digital artwork gains maximum audience engagement. Ways to ensure this can include the use of btricksb or shortcuts, such as those used in one of the artworks that were physically embedded in statues around the gallery space, with which the audience interacted. In this way, curators of these types of works can offer guides to those who do not have an instinctive engagement with the artworks.

Through participating in the workshops organised by this project, the members learnt about new ways of understanding the city, influencing their approach to the project which considered our relationship both to sites of remembrance and those we remember. Emily Gee, Acting Communities Manager, FACT (Foundation for Art and Creative Technology)

FIGB 3. Ricardo Miranda Zuniga, Geography of Being at FACT

FIGB 3. Ricardo Miranda Zuniga, Geography of Being at FACT

Social Media for Curation and Engagement

The project aimed to explore ways of capitalizing on the current boom in social media to encourage audiences to engage with the artworks. Social media was conceived of as a way to develop feedback loops, and to help the artworks reach out beyond the gallery space b one of the constant debates that has underpinned both curatorial discussions about digital art, and practitionersb approaches to their own practice. The social media platforms trialled during the project to achieve this end included Wordpress, Twitter, Buffer, Storify and Facebook.

One of the most interesting challenges for the project was the use of social media as a form of curation. Whilst there is by now a relatively large body of research undertaken on the curation of tweets in the sense of saving tweets that occur organically around a particular event or topicB [3], there is very little existing scholarship to date on how to use Twitter as an effective curation tool for pre-selected artistic images. In the case of our project, Twitter Galleries were designed to run throughout two months of the project to enable the sharing of exclusive artwork images, and gave the public a rare glimpse into an artwork as it evolves. The public had the chance to feed into the artwork themselves, by proposing other images that could be incorporated, and were encouraged to comment on and vote for their favourite image. A live Q&A Twitter chat with the artist was scheduled, as a way of creating a particular btime windowb of interest around the events, and also as a way of combining face-to-face presence with virtual interaction.

The Latin(o) American Digital Art projectbs presentation to us on Twitter curation and social media for audience engagement was of particular benefit for us, as it was of direct relevance to discussions around innovative means of delivery and dialogic spaces. Rosana Carrete, Cabildo of Montevideo Museum and Archive, Uruguay

Drawing on the experience of the project, interviews with the artists, Twitter statistics, statistics drawn from our main partners[4], discussions with curators, and questionnaires, the benefits of Twitter curation were found to be:

- Easily trackable engagement with the artworks. Twitter analytics provides for a certain level of granularity, allowing curators to track engagements, including Impressions (i.e. views of each tweet), Engagements, and Engagement Rate. These enable curators to see which image has been the most popular, but also to cross-check this against other data, allowing one to see, for instance, whether tweets at certain times of day, or with certain keywords in the descriptor, incited more or less engagement.

I now appreciate Twitter as another medium for artistic dissemination. I can see that it has potential to be both useful and to reach a large number of people. Participant in the Ciudades en diálogo workshop, Buenos Aires

- Engagement much less cumbersome than traditional bexit surveyb. The use of Twitter as a curating tool meant that feedback could be provided by the general public immediately, through favourites and re-tweets. This has advantages over the traditional bexit surveyb which can often be cumbersome, and which audiences can often be reluctant to fill out. The use of social media allows for more flexible and dynamic feedback, and also ensures that feedback can be suited to individual timeframes, since engagement can happen at any moment during or after the exhibition.

- The artwork as dynamic. The use of Twitter as a way of curating the images of the artwork in progress helped foment the idea that the public could become co-creators. Twitter can be a way to encourage participatory art works, whereby, making use of the potentials of digital technologies, spectators are enabled as active co-creators of the work of art and have increased input into the work itself. This feedback into the artwork also has advantages for the planning of subsequent events, where audience reactions about delivery methods or improvements can then feed into new iterations of the artwork.

- Dissemination over time and space. Dissemination of the artworks via Twitter enabled a greater temporal reach, meaning that those not able to attend in person could view the art works. It also enabled engagement over a wider timeframe, and the ability to track these engagements over time.

The challenges of Twitter curation were found to be:

- Telling a narrative. The curation of the artwork through Twitter meant that the conventional paraphernalia surrounding an artwork, such as an explanatory text or gallery catalogue, were not available to sit alongside each image. Although these elements were provided elsewhere (including in our programme notes, FACTbs brochure, the Independents Liverpool Biennial brochure, websites, and in many other sources), these could not be reproduced each time within each tweet. A narrative thus had to be created that could be sustained over a month-long period, without this narrative becoming repetitive, such that a viewer could come to an individual tweet and still understand it. Strategies to achieve this included the development and employment of hashtags to create a coherence across the tweets, judicious use of links to sites with further information, and reminders of the overall project within the tweets.

B This project is a template for how to be educationally inclusive as a conduit between artist and audience, by creating participatory interactions and experiences within the creative process. It is a way to challenge the perceptions of the audience and create an exciting forum for discussions about their cultural experiences. Simon Yorke, Independents Liverpool Biennial

- Limitations of the character length. The limitations of the Twitter platform as regards character length are by now well documented. Our approach to this challenge was to build on ideas behind new electronic literary genres such as Twitter poetry, or Twitter microfiction which posit this limitation as a creative one.[5] Making use of various shortcuts such as compressed links using bitly, and varying the mentions of our partners and venues, were ways in which creative engagement with this restraint were achieved.

- Preparedness of the Twitter community. Although social media use is widespread, with Twitter being one of the most popular platforms, critical thinking and artistic engagement through Twitter is a new concept for many. A significant challenge lay in ensuring that the wider public was prepared for, and understood how to engage with, what the project was proposing. This challenge of changing behaviours, and of having an impact on the way in which people use and view social media, was addressed by suggesting ready-made hashtags to encourage engagement, and by holding a series of face-to-face events including presentations and workshops at which the public were introduced to these new concepts and uses. A further solution was to find new ways (such as incentive prizes) to make people more active in the social media used as a curatorial space. .

FIG 4 Marina Zerbarini Tejido de memoria at FACT

FIG 4 Marina Zerbarini Tejido de memoria at FACT

Future possibilities for Europe-Latin(o) American artistic collaborations: Non-Anglophone Art in the UK

The project aimed both to showcase cutting-edge digital art that was rooted in its Latin(o) American context, and, at the same time, draw out interconnections with Liverpool, and with other regional and national contexts [FIG 2]. In so doing, the projected aimed to address a relative under-representation of Latin Americans in festivals and exhibitions of new media art within the UK. Examples of digital media practice are often Anglophone, hence the project attempted to raise the profile of Latin American digital artists, bring their work to a UK audience, and provide for innovative forms of engagement with their practice.

The principle ways of achieving this involved close collaboration with, and support from, the curators at FACT and at the Independents Liverpool Biennial. The willingness of curators to take a risk and to engage with non-Anglophone artists was key to the success of the events. Publicity also played a significant role, with the advertising of the artists and their work through the print media (programmes and schedules of events) and digital media (website, blog and Twitter) of both organizations. The strong endorsement of these artists through these two organizations meant that audiences trusted the brand, and were so more likely to accept and engage with these non-Anglophone artists. Other ways in which this collaboration was facilitated is through shared information for future collaborations, including the Latamnetart delicious database created by the project, which provides a searchable tool not just for research, but for curators to browse and to select Latin American artworks and artists for future exhibitions and events.

The principle benefits were found to be:

- Enrichment of the current offering. The inclusion of Latin American artists within the various venues and events brought a new audience to their work. FACT already plays a leading role in exhibiting international artists, and the inclusion of this exhibition on Latin American digital art provided a sustained focus on this region. The Independents Liverpool Biennial conventionally showcases predominantly local talent, so the inclusion of Latin American artworks brought a new perspective to the organization.

- Bringing practices into dialogue. The opportunity to showcase these artists also brought with it the opportunity to share expertise and best practice. In particular, the practices of tactical media, which have been well developed and theorized in a Latin American context, provide favourable opportunities for sharing practices. The strategic use of low-tech, for example, which informs much of the work of artist Brian Mackern, formed a central feature of the workshops held with the Veterans in Practice.

- Building and Developing Networks with Latin(o) American Partners and Institutions. The development of the events led not only to collaboration with institutions in Liverpool, but to those based in other parts of the globe, including Latin America. Benefits include possible exchanges in the future, reciprocal ideas, and co-sponsoring of events.

The challenges were found to be:

- Linguistic and cultural challenges. The issue of bringing non-Anglophone artists to exhibit and run events in the UK inevitably raises issues regarding linguistic and cultural competence. On a purely practical level, ensuring that any texts not originally written in English are translated, and that interpreters are available for artistsb talks where these are not given in English, is essential for ensuring a basic understanding of the works. Yet on a more profound level, it is also important to consider the linguistic and cultural awareness of the target audiences as a whole, and to this end, ensure that linguistically- and culturally-informed ushers are on hand throughout the exhibition to ensure the audience is given full access to understanding the works and their cultural context. .

- Maintaining the intellectual and geographical coherence. Given the site-specificity of the artworks, and their rootedness within a Latin American context, a particular challenge lay in maintaining a balance between ensuring a coherent offering on the one hand, and on maintaining the site-specificity on the other. Ways to deal with this challenge included developing a focus around a particular theme b the notion of the cityspace b and then allowing that theme to help establish the connections, rather imposing an artificial coherence that would have flattened out the distinctiveness of each artwork. Also, collaboration with local community media groups (such as Veterans in Practice in the case of this project), can help establish a coherence and connections across different cityspaces. .

FIG. 5 Brian Mackern Santa Rosa altar at FACT

FIG. 5 Brian Mackern Santa Rosa altar at FACT

FIG 6. Brian Mackern, This Too Shall Pass

FIG 6. Brian Mackern, This Too Shall Pass

Notes

[1] See Appendix A of the online version of this Policy Document for copies of these statistics.

[2] See the book of the exhibition for more details: Claire Taylor, Cities in Dialogue (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2016)

[3] See for instance, Julian Stallabrass, Internet Art: The Online Clash of Culture and Commerce (London: Tate Publishing, 2003), p.120; London, Barbara. “Out on the Edge”, in Dieter Daniels and Gunther Reisinger, eds., Net Pioneers 1.0: Contextualizing Early Net-Based Art (Berlin: Sternberg), pp.199-207 (p.204-206) and Christiane Paul, Digital Art (London: Thames & Hudson, 2008), revised edn (23-24).

[4] See Timothy Arnold and Walker Sampson, ”Preserving the Voices of Revolution: Examining the Creation and Preservation of a Subject-Centered Collection of Tweets from the Eighteen Days in Egypt”, American Archivist, 77:2 (2014), 510-533.

[5] See for instance Jason Camlot, “tickertext1: New Media Poetics of Occasion”, Canadian Journal of Communication, 37, 167-172. :

About the Authors Claire Taylor is Professor of Hispanic Studies in the Department of Modern Languages and Cultures at the University of Liverpool, UK. Her research specialisms include Latin American hypermedia narrative, net art, and literary blogs, with a particular interest in the works of Belén Gache, Guillermo Gómez Peña, Brian Mackern, Ricardo Miranda Zúñiga, Eduardo Navas, Marta Patricia Niño,B Jaime Alejandro Rodríguez and Marina Zerbarini.